Early Records: Cave Paintings to Illuminated Manuscripts

Earliest Beginnings: Cave Dwellers, Pictographs and Ideograms

The beginning of human record keeping is due, largely in part, to early humans. Symbols carved on items, such as Australian aborigine message sticks, serve as the earliest external memory devices (Valentine, 2012.) As a means of self expression, ancient drawings and paintings (cave paintings) were left behind by European cave dwellers to express the poignant experiences of the peoples who created them (McMurtrie,1943.) These images, referred to as pictographs (pictures that represented a memory or conveyed suggestions) began to develop into ideograms, pictures that represented ideas produced from these objects (McMurtie,1943). Ideograms would become a way for early humans to express thought through writing (McMurtrie,1943.) It could be said that the history of the book started with Sir Arthur Evans' 19th century discovery of a set of linear pictographs in Crete (McMurtrie,1943.)

Prehistoric cave painting in Lascaux (Izzotti, n.d.)

Papyrus, Parchment, and the Ancient World

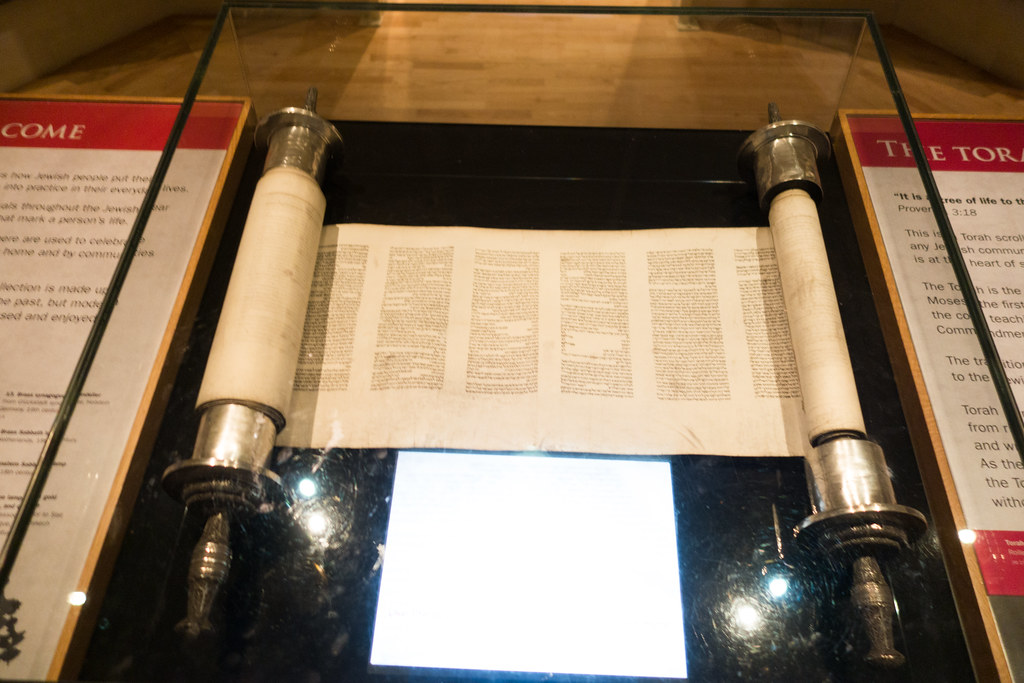

Egypt is often considered the birthplace of the physical book. After using materials such as bone, metal, clay, and stone to write on, the Egyptians discovered that they could create paper from papyrus, a type of reed that grew plentiful in the region. (University of Minnesota Libraries, n.d.) Egyptians used these reeds to make the papyrus as well as pens to write with (University of Minnesota Libraries, n.d.) The Egyptians would create scrolls by attaching multiple sheets of papyrus together, either by the use of adhesives or stitching (University of Minnesota Libraries, n.d.)

Torah Scroll (Quine, 2017)- CC BY 2.0

Parchment would be developed later as an alternative to papyrus after growing frustrations with other powerful entities of the ancient world, such as Greece and Rome (University of Minnesota Libraries, n.d.) Parchment could be made from animal skins instead of reeds and this weakened Egypt's grip on the paper trade (University of Minnesota Libraries, n.d.); the reeds that papyrus derived from only grew in Egypt (University of Minnesota Libraries, n.d.) Parchment was also more useful than papyrus because it was more durable and both sides of the parchment could be used for writing (University of Minnesota Libraries, n.d.). The use of papyrus and parchment would lead to the invention of the next closest relative to the modern book.

Wax Tablets and Codices

The next significant development that brings us closer to the modern book comes in the form of wax tablets, wooden tablets that could be written on that were coated with wax (Valentine, 2012.) 100-300 CE saw the birth of the Codex, an early precursor to the modern book (University of Minnesota Libraries, n.d.)

Codex Purpureus (Codex Rossanensis); Last Supper and Christ Washing the Disciples' Feet

Romans would fold sheets of parchment together until eight sheets could be made and then they would sew them together between two pieces of wood (Valentine, 2012); this resulted in a text that was easier to handle (reading a scroll required two hands), less costly to produce, and more portable, making it easier to store (University of Minnesota Libraries, n.d.) Later on, Vellum, a type of paper made from calf skin, would be used as well. The use of the codex would finally overtake the use of scrolls in 500 CE (University of Minnesota Libraries, n.d.); while scrolls remained popular for non-religious works until 500 CE, the rise of Christianity and the popularity of the codex format for Christian texts made it the dominant form of publication during that time (University of Minnesota Libraries, n.d.)

References:

Izzotti, A. (n.d.). Prehistoric cave painting in Lascaux. [Image]. Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved from

https://www.britannica.com/place/Lascaux

McMurtrie, Douglas, C. (1943). The book; The story of printing and bookmaking. Oxford University Press

(middle of the 6th century). Codex Purpureus (Codex Rossanensis); Last Supper and Christ Washing the Disciples' Feet; folio 3r.

[manuscript]. Retrieved from https://libproxy.highpoint.edu/login?url= library.artstor.org/#/asset/SCALA_ARCHIVES_1039931483

Quine, Thomas (2017.) Torah Scroll: London Jewish Museum, 2017 [Image]. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/quinet/28634085987

University of Minnesota Libraries (n.d.) 3.2: History of Books. University of Minnesota.

https://open.lib.umn.edu/mediaandculture/chapter/3-2-history-of-books/

Valentine, Patrick M. (2012). A social history of books and libraries from cuneiform to bytes. The Scarecrow Press, Inc.

Additional Readings

-

Cave of Lascaux: The final photographs byCall Number: 2nd Floor - Folio Collection Folio 709.011209364 R89c 1987ISBN: 9780810912670Publication Date: 1987-05-01

-

Dawn of Art: The Chauvet Cave : the oldest known paintings in the world byCall Number: 2nd Floor - Folio Collection Folio 709.0112094482 C39da 1996ISBN: 9780810932326Publication Date: 1996-03-30

-

Egyptian papyri and papyrus-hunting byCall Number: 3rd Floor - General Collection (001-099) 091 B15eg 1925Publication Date: 1925

-

Social History of Books and Libraries from Cuneiform to Bytes byCall Number: AVAILABLE ONLINEISBN: 9780810885714Publication Date: 2012-01-01